Subterranean catfishes live in Kerala’s limited groundwater aquifers. These fish survive in darkness with low oxygen and nutrition levels. When homestead wells are dug or cleaned, these elusive fishes occasionally appear.

Locally-trained citizen scientists found catfish in Kerala dugout wells and gave them to scientists as part of a long-term experiment. Scientists collected catfish from wells and aboveground tanks. Scoop nets and baited traps were utilized in shallow wetlands, water channels, home gardens, and plantations.

The Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS), Shiv Nadar University in New Delhi, and Senckenberg Museum in Germany discovered a new cryptic species. The tiny fish was named Horaglanis populi to honor the citizen scientists who provided information and specimens.

Ghosts: Subterranean fishes and Horaglanis

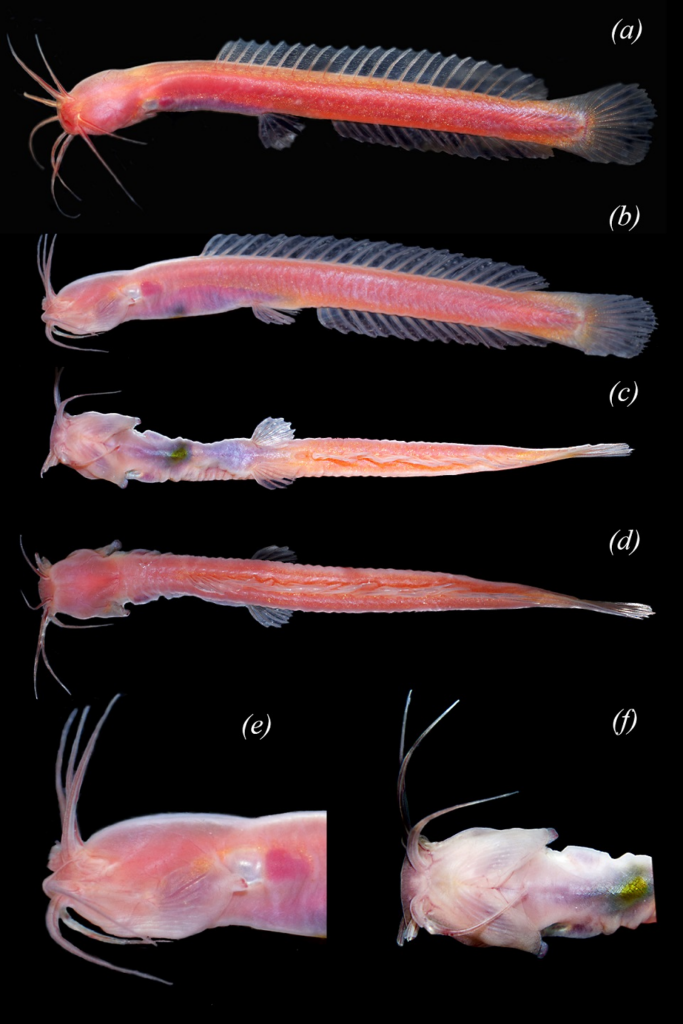

Kerala’s lateritic aquifer systems are home to tiny, eyeless Horaglanis fishes. The species’ permeable skin exposes its blood, giving it a blood-red color.

“Because of a lack of pigment many cavefish are white or pink in colour,” says Prosanta Chakrabarty, Louisiana State University professor of evolutionary biology and ichthyology (fish study). “If ‘Satan’ wasn’t already taken by a Texas catfish I would have suggested it for this species,” he says. “I’m envious and hope to see these alive.”

All other aquifer-dwelling fishes live in limestone strata, save Horaglanis. Horaglanis is confined to Kerala south of the Palghat Gap, a biogeographic barrier in the Western Ghats Mountains.

Kerala’s lateritic terrain attracts subterranean fish worldwide. Laterite is an iron- and aluminum-rich soil and rock found in humid tropical climates. Southwest India uses lateritic aquifers for domestic and agricultural water.

Raghavan says this result suggests that subterranean fish species richness is still underestimated and intensive investigations are needed to comprehend it.

Milton Tan, a non-study assistant research scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, agrees. Tan says, “We still don’t have a good idea of how many different kinds of these subterranean catfishes there are. “Discovering a new species adds to our understanding of the universe.”

10% of 289 subterranean fish species, including 53 catfishes, live in aquifers. Raghavan says, “There are a few enigmatic blind catfishes, mostly in the Americas—some of these include members of the genus Satan, Prietella, Trogloglanis, Phreatobius.

Chakrabarty says that Indian cavefishes are the most intriguing because they have been poorly investigated compared to China, Brazil, the U.S., and Mexico, where over 100 species are known. “Thanks to local researchers like Rajeev Raghavan and his students and collaborators we are learning so much about what was once hidden, these ghosts of surface-dwelling ancestors.”

10 endemic species in five genera—Aenigmachanna, Horaglanis, Kryptoglanis, Pangio, and Rakthamichthys—have been found. Three of the four Horaglanis species were previously known.

These fishes are rare and unprotected. These fishes are threatened by unregulated dugout well water extraction. Seawater intrusion into aquifers is a hazard for Horaglanis fishes found within 30 km of the shore. Groundwater pollution and lateritic soil mining for development are other issues.

Genetically varied but similar-looking

Neelesh Dahanukar, co-author of the study and assistant professor at the School of Natural Sciences, Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, Delhi-NCR, says that when two or more ancestral species populations are isolated for a long time, they can become genetically different and form a new species. “Because isolated populations may inhabit different habitats, they can accumulate morphological changes [changes in external appearance] due to adaptation to surrounding environmental conditions.”

These exterior differences define species. “Our genetic analysis suggested that H. populi was genetically much different from all the other known species, but we were surprised that there were no morphological differences to distinguish it,” adds Dahanukar. “Despite high genetic divergence, all four species have no morphological differences that can distinguish them. Thus, only genetic barcoding can distinguish these species.

Citizen science

Raghavan’s team explored Kerala’s lateritic terrain for six years using citizen science. In workshops and focal-group discussions, the researchers asked villagers to share species information, photos, and videos. They also learned how to conserve the species. These citizen scientists helped the researchers add 47 Horaglanis locational records.

The team expects to find more local species. Raghavan stresses public participation in uncovering new unusual species. “We need to educate the public and citizen scientists about these unique species, where they are likely to occur, how they can be collected and made available for research, and how their habitats can be protected.”

Tan emphasizes the relevance of citizen science in identifying new species. “Commendably, the authors seem like they worked really hard to connect to citizens in the region that would be interested in helping this project,” he says. “The work would be difficult or impossible otherwise. Citizen scientists have several opportunities to identify new species. Even sharing animal photos to iNaturalist helps find new species!”